There are approximately 7,000 languages spoken worldwide. You are aware of the world’s major languages – Chinese (Mandarin), Spanish, English, Hindi, Arabic, Portuguese, Russian, and Japanese, to name a few.

About 96% of the world’s population speaks about 4% of the world’s languages, leaving the vast majority of other little-known languages on the verge of dying and disempowering their native speakers. Linguistic diversity reflects a lot of things that are more than accidental historical splits. Languages play as essential building blocks community and cultural identity, and authority.

Due to the globalization of dominant cultures, colonization, and homogenization, indigenous groups are now being pushed aside and marginalized. As a result, more and more of these minorities are added to the sad statistic of people with dying culture and heritage. Some of the most crucial symptoms of the loss of culture and heritage are dying and forgotten languages. It’s reason enough why we should reclaim and revive them.

Language revival, or language revitalization, attempts to resurrect a declining language or bring back a formerly extinct language.

The great news is that some endangered or extinct languages have been given attention. Many linguists and academics attempt to regain extinct or endangered languages some of their lost glory. However, Hebrew is the only one that has attained the most substantial success, with millions of speakers worldwide. The other revived languages only experience limited success – but big or small, it’s a step forward nonetheless. One only hopes that continuous efforts ensure that these revived languages should stay for good and be spoken by future generations.

Here are five examples of languages that have been currently revived or resurrected.

1) Ainu (Hokkaido, Japan)

The Ainu language is spoken on the northern island of Hokkaido, Japan. Ainu is considered a unique isolate with no genealogical relationship to any other language family, making it a “moribund language.” It also has no written language, so it is mostly written in either the Japanese katakana or hiragana script.

There are around 24,000 Ainu people today, many of whom are of mixed ancestry. But a majority of them have assimilated to the dominant Japanese culture and language. As a result, there are now only two surviving fluent Ainu speakers as of this writing. Some people of Ainu ancestry speak the language but only partially or infrequently.

The Japanese government granted the Ainu people indigenous rights only recently, and as a result, the Ainu language has only recently come to many linguists’ attention. Many linguists in Japan and elsewhere are working to revive this endangered language. Shigeru Kayano (1926 – 2006), one of the last native Ainu speakers, launched efforts that became instrumental in the revival of Ainu. While Ainu is not yet regularly taught in most schools in universities, it is offered at several universities and language centers, especially in Hokkaido. Tokyo’s Chiba University also offers studies on Ainu culture, language, and literature.

2) Cornish (Cornwall, United Kingdom)

The Cornish language began to die out in the 4th century, but its decline even hastened further in the 13th century. It lost its official status following the English (Protestant) Reformation but lingered in parts of West Cornwall until the 18th century. The last Cornish speaker is said to have died in 1891, which seemed to mark the death of this language.

But in the late 19th century, there was a resurgence of interest towards Cornish, primarily due to the Celtic language revival movement. There were some records of the language (mostly in its medieval form) to allow it to be revived to an extent in the 20th century. Since then, the revival of the Cornish language has been quite strong. Speakers of Cornish reside primarily in the county of Cornwall, which has a population of 563,000 (2017 estimate). Some Cornish speakers live outside Cornwall, especially in the Cornish diaspora and other Celtic regions.

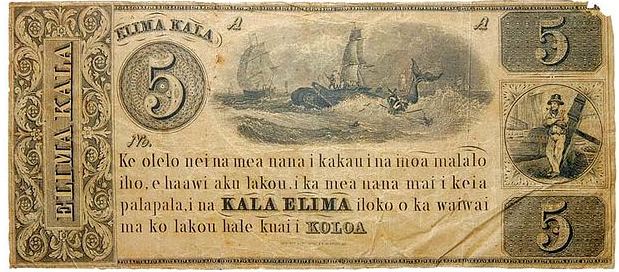

3) Hawaiian (Hawaii, USA)

Hawaiian, a Polynesian language, has suffered a significant decline since the arrival of the European colonists. On six of the seven inhabited islands in Hawaii, the language has been displaced by English. As a result, Hawaiian is no longer used as a daily language. The only exception is Ni’ihau, where Hawaiian has never been displaced or endangered and is still used almost exclusively.

By the 1980s, there had been only a few hundred Hawaiian speakers, posing a great risk to the indigenous Hawaiian culture. It seemed to be a wake-up call for the Hawaiians to make an effort to revive this beautiful language. Local communities established several Hawaiian-language “immersion” schools for children whose families wanted to introduce (or retain) the Hawaiian language into the future generations. This approach worked. Today, there are about 24,000 native Hawaiian speakers.

4) Hebrew (Israel and Jewish diaspora)

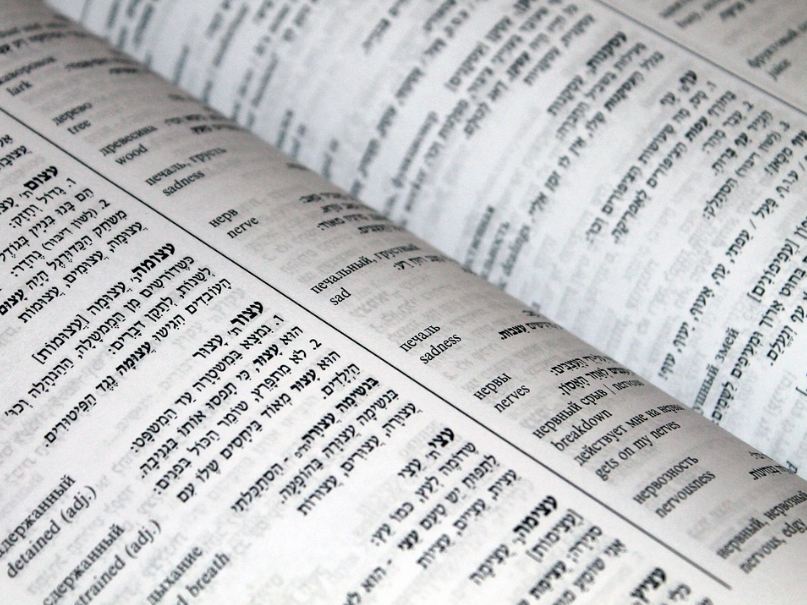

So far, Hebrew is the only example of a successfully revived language. The only surviving member of the Canaanite group of languages, Modern Hebrew is based on Biblical Hebrew, which existed around 200 CE and gradually developed into a liturgical and literary language. But following the failed Bar Kochba revolt during the Roman Empire, ancient Hebrew gradually declined and ceased to be a language for daily communication. It lingered on into the medieval period as a Jewish liturgical, literary, and commercial language. But despite that, ancient Hebrew was considered too archaic or sacred for regular, day-to-day communication.

Modern Hebrew’s revival truly came along with the rise of Zionism in Europe in the 19th century and Mandatory Palestine in the 20th century. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, a 19th-century Jewish lexicographer and newspaper editor, was the driving force behind Hebrew’s revival into the modern era. Hebrew was resurrected as a spoken and literary language. It eventually became the language among the Yishuv, a group of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel during the pre-state era, and now the State of Israel.

Hebrew is the official language of the State of Israel. It now has approximately nine million speakers, five million of whom are native speakers.

5) Māori (New Zealand)

Māori is a language spoken among the indigenous groups in New Zealand. Until the Second World War, most Māori people spoke it as their primary language. But by the 1980s, less than 20% of Māori people spoke the language fluently or well enough to be classified as native speakers.

The dominance of other languages is usually blamed for the decline of indigenous languages. In this case, Māori has been displaced by English, as the latter is compulsory in schools. Increasing urbanization has also driven younger Māoris to be disconnected from their extended families, especially their elder relatives who still hold on to the traditional Māori values. Even many of those people no longer speak Māori at home, resulting in the younger generation of Māoris not knowing their ancestral language.

In response, several initiatives have been taken to revive Māori as a spoken language. In the 1980s, Māori leaders launched Māori-language recovery programs, such as the Kōhanga Reo movement, which immersed babies in Māori until they reached school age. The efforts paid off. In 1989, Kura Kaupapa Māori — primary and secondary Māori schools – were given government support.

While the numbers are not officially established, there are some 50,000 people who claim to speak Māori fluently or very well.