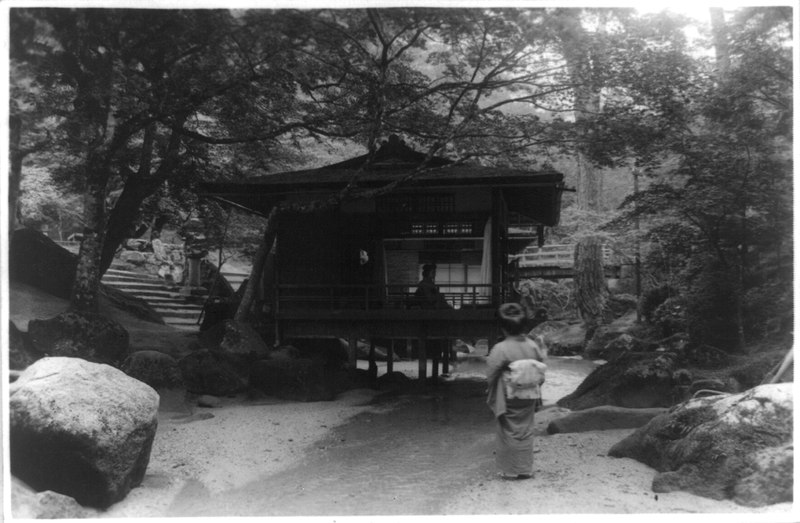

Imagine stepping onto the smooth stone path leading you through a tranquil garden to the serene beauty of a traditional Japanese tea house. You’re about to embark on an insightful journey through the elegant world of Japanese architecture, from the majestic temples that touch the sky with their gently curved roofs to the intimate tea houses that invite contemplation and harmony. Each structure tells a story of cultural values, aesthetic principles, and a deep respect for nature.

As we explore the intricacies of design and the historical significance of these spaces, you’ll discover how traditional Japanese architecture has influenced modern design and continues to inspire a sense of peace and beauty in our fast-paced world. Join us in uncovering the secrets behind the simplicity and elegance that define these architectural wonders.

The Essence of Japanese Temples

Exploring the essence of Japanese temples, you’ll find that each structure, from the iconic Ginkaku-ji Silver Pavilion to the tranquil Ise Shrine, embodies centuries of spiritual and architectural wisdom. These temples, grounded in history as far back as the 15th century, aren’t just buildings. They’re a testament to the deep-rooted cultural and architectural importance that has shaped Japan’s identity. The meticulous detail in temples like the Katsura Imperial Villa reveals a reverence for traditional Japanese design principles, emphasizing harmony between the built environment and the natural world.

This connection to nature, the pursuit of tranquility, and the spaces designed for spiritual practices, highlight the broader cultural significance of Japanese temples. They’re not merely places of worship but are pivotal in understanding the Japanese way of life, where architecture and spirituality intertwine seamlessly. The influence of traditional Japanese temple architecture on modern design further underscores its timeless appeal and global relevance. It’s a bridge between past and present, showcasing how ancient principles can inform contemporary spaces, highlighting the enduring legacy of Japanese temples in the architectural world.

Unveiling the Chashitsu

Diving into the world of chashitsu unveils a realm where the art and ritual of Japanese tea culture come to life, offering a serene sanctuary for contemplation and connection. These tea houses, whether standalone structures or nestled within gardens, are steeped in the traditions and historical influences of figures like Sen no Rikyu and Ashikaga Yoshimasa. They’re not just buildings; they’re a testament to the beauty of traditional Japanese architecture and a deeper philosophy of simplicity, nature, and tranquility.

| Feature | Function | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Mizuya | Tea preparation | Enhances the ceremony’s flow |

| Tokonoma | Art display | Cultivates aesthetic appreciation |

| Shoji Panels | Light modulation | Creates a serene atmosphere |

| Chabana | Seasonal flowers | Connects with nature |

| Tokobashira | Architectural pillar | Symbolizes strength and beauty |

In exploring chashitsu, you’re not just observing an architectural marvel; you’re stepping into a space where every element—from the layout to the materials like Japanese red pine used in tokobashira—play a crucial role in creating a peaceful and contemplative setting. It’s here, in these tea houses, that the traditional Japanese ethos of harmony with nature and thoughtful simplicity is fully realized.

Key Elements of Design

You’ll find that the design of traditional Japanese tea houses centers on elements like tokonoma, shoji panels, and tatami mats to foster a serene and meditative space. These components aren’t just decorative; they’re deeply imbued with cultural significance and a philosophy that prioritizes harmony, simplicity, and the natural world. In your exploration of these spaces, you’ll come to appreciate how each detail contributes to the overall experience of the tea ceremony.

Key elements include:

- Tokonoma: A focal point for art display, usually featuring chabana (tea flowers) and seasonal hanging scrolls. This alcove is a testament to the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, emphasizing beauty in imperfection and transience.

- Shoji paper panels: These translucent screens allow natural light to filter into the room, creating a soft, diffuse atmosphere. Their lightweight nature also embodies the Japanese principle of simplicity and functionality.

- Tatami mats: Laid out in precise configurations, these mats define the seating arrangements and contribute to the room’s aesthetic with their natural color and texture. Sitting on tatami during tea ceremonies encourages guests to adopt seiza, a traditional kneeling posture that promotes mindfulness and respect.

Through these elements, the design of a tea house meticulously sets the stage for a transformative tea gathering, emphasizing a connection to the moment and the environment.

Historical Significance

Delving into its rich history, Japanese tea houses, or Chashitsu, have been a cornerstone of cultural tradition since the Muromachi period, shaped by influential figures like Ashikaga Yoshimasa and Sen no Rikyu. These spaces, whether standalone or nestled within serene gardens, have always been more than just places to enjoy a cup of tea. They’re imbued with a sense of ceremony and a deep connection to nature, designed to enhance the ritual of tea gatherings.

Ashikaga Yoshimasa, a notable shogun, and Sen no Rikyu, a tea master, both played pivotal roles in the evolution of Chashitsu. Their influence is evident in the architectural details, from the simplistic beauty of the gardens that lead you into the tea house, to the very layout that dictates the flow of the tea ceremony.

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Gardens | Designed to reflect the natural beauty and induce a sense of tranquility. |

| Entrances | Crafted to symbolize the transition from the external world into a space of harmony. |

| Chabana Arrangements | Floral decorations that embody the beauty of imperfection. |

| Tokobashira Structures | Pillars that represent the natural aesthetics of wabi-sabi. |

These elements, combined with the materials and design principles of Chashitsu, underscore the historical and cultural significance of the Japanese tea ceremony, making it a profound experience that goes beyond mere aesthetics.

Modern Influence and Legacy

The simplicity and aesthetic appeal of traditional Japanese architecture, from teahouses to temples, have significantly influenced modern architects and designers worldwide. In the 1950s and 60s, this admiration for the understated elegance and functional beauty of Japanese design led to a wave of innovative architecture that still resonates today. Werner Blaser’s work, in particular, served as a bridge, introducing the Western world to the essence of Japanese aesthetics, profoundly impacting figures like Mies van der Rohe.

You’ll find the modern influence of traditional architecture in various aspects, including:

- Contemporary tea house designs, such as The Glass Tea House – Kou-An and Kengo Kuma’s Tea House, which marry traditional elements with avant-garde architectural techniques.

- Influential publications by Werner Blaser that explored the Japanese spirit in architecture, impacting both art and design in the West.

- Collaborations with renowned architects like Christian W. Blaser, Inge Andritz, and Tadao Ando, which have enriched and perpetuated the legacy of traditional Japanese design principles in modern projects.

This blending of traditional architecture with contemporary innovation not only honors the past but also ensures its relevance and inspiration for future generations of architects and designers.

Conclusion

As you’ve delved into the world of traditional Japanese architecture, from the tranquil temples to the intimate tea houses, you’ve seen how deeply design and culture intertwine. You’ve uncovered the significance of every element, from the serene roji gardens to the modern Glass Tea House – Kou-An. This journey reveals not just the historical importance but also the evolving legacy of these spaces. They’re not just structures; they’re living embodiments of Japanese aesthetics and philosophy, ever adapting and enduring.