Remember the olden days when the phrase “just Google it” wasn’t a thing yet? Back then, when there was no Wikipedia or WebMD to look up stuff yet, we have the trustworthy encyclopedia. It’s nostalgic to remember the days when you’re doing your research for homework about the Vietnam War, and you pick the “V” volume of your encyclopedia set. If that’s familiar, that’s great. For some families, having a set of encyclopedia on their shelves is more of a status symbol – to show that a family had taste, money, some pretense to intellect or a desire to be seen that way. Especially if the set of encyclopedia is Encyclopedia Britannica.

In 2012, Encyclopedia Britannica announced that they would stop producing hardbound, paper copies of their reference books. It’s an end of the era, but it’s one of the sad realities of the digital age. But Encyclopedia Britannica still goes on, focusing primarily on online encyclopedias and educational curriculum for schools.

Though hardbound encyclopedias aren’t popular today as they were before, you might have been interested in how it came to be. Here’s the interesting history of the most venerable standard-bearer of facts in the world, the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Origins

Encyclopedia Britannica is the oldest English-language general encyclopedia, first published in 1768 in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was a brainchild of Scotland printers and engravers Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell. They also had an editor, William Smellie. The first edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica had three volumes. They are two guys with no formal training and a drunk editor who managed to create a resource for useful and practical information.

While the encyclopedia grew to be considered as a reputable source of factual information for the last few decades, it had a humble and sometimes factually-challenged roots. The 1768 version contained some guesses, like for instance, the entry for California was spelled with two L’s, it stated that it’s a large country of the West Indies, and it was uncertain whether it is an island or a peninsula.

History of Encyclopedia Britannica

The Britannica has issued 15 editions. The history of the encyclopedia can be divided into five different eras, categorized by changes in management or re-organization of the dictionary. The last edition underwent a massive re-organization during 1985, but the latest and most updated version was still known as the 15th. Also, the 14th and 15th were the only editions edited every year throughout publishing, so later printings of each were different from early ones.

Earliest Editions – 1st to 6th (1768-1826)

During the first editions, Britannica was managed by its founders. The first edition was published between December 10, 1768, to 1771 in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was published as the Encyclopædia Britannica, or, A Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, compiled upon a New Plan. Britannica was partly conceived as a conservative reaction to the French Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot, which was widely viewed as heretical. Ironically, the French encyclopedia only began as a French translation of the popular English encyclopedia at the time: the Cyclopaedia by Ephraim Chambers that started publishing in 1728. Macfarquhar and Bell were inspired by the Scottish Enlightenment and thought that the time was ripe for a new encyclopedia.

The new encyclopedia aimed to be an excellent reference book for providing educational material. The founders’ idea to set Britannica apart was to group related topics together into longer essays, and are alphabetically organized. Previous English encyclopedias generally had related items listed separately in alphabetical order. The Britannica became one of the most enduring legacies of the Scottish Enlightenment.

The first edition was a success, so the second edition that begun in 1776 was a more ambitious project. While the first edition contained three volumes, the second one expanded to 10. It added history and biography articles, but Smellie declined to be the editor. Macfarquhar took the role himself and hired pharmacist James Tytler as a co-editor.

Colin Macfarquhar died while creating the third edition, and Andrew Bell bought the rights to the Britannica from his partner’s heirs. The third edition doubled the scope of the second one. Andrew Bell passed away one year before the 4th edition was finished. In 1815, his heirs began to produce the fifth edition, but sold the rights to Archibald Constable. He had Dr. James Millar as editor.

The fifth edition was supposed to be a reprint of the fourth, but there is virtually no change in the text. After securing sole-ownership rights, Constable began working on a supplement to the 5th edition, which was later known to be a supplement to the fourth, fifth and sixth editions. In the sixth edition, almost no changes were made to the text, and was basically a remake of the 5th edition with minor updates. It was thought that the sixth one only existed for the need to remove the long “s,” which had gone out of style at the time.

Because of the encyclopedias being outdated, Constable went bankrupt in 1826, and the rights to Britannica were sold at an auction. Britannica was bought by a partnership of four men led by Adam Black, but not long after, Black bought out his partners and transferred the ownership to a publishing firm of A &C Black in Edinburgh.

A & C Black Editions – 7th to 9th (1827-1901)

The supplement to the 4th, 5th, and 6th edition clumsily addressed issues, often referring back to the encyclopedia. Because of this, the readers had to look for everything up twice. The 7th edition fixed this problem by creating an entirely new edition.

The 7th edition, which began publishing from 1830 to 1842, was a new work – not a revision of the earlier editions. It consisted of 21 numbered volumes, and it was the first edition to include a general index for all articles. The index was 187 pages, and it was either bound together with Volume I or bound alone as an unnumbered volume. Many illustrious contributors were hired for this volume.

The same style was carried out on the 8th edition, but not on the 9th.

The 8th edition was a thorough revision of the Britannica, and a total of 344 contributors created the edition, including Britannica’s first American contributor.

The 9th edition, published in 1875 to 1889 in 25 volumes, was dubbed as the “Scholar’s Edition.” It was lauded as high points for the scholarship, and it featured another series of illustrious contributors like Lord Rayleigh, Thomas Henry Huxley, William Michael Rossetti, and Algernon Charles Swinburne. There were around 1,100 contributors altogether, and a handful of them were women.

Compared to the preceding editions, the 9th edition was also far more luxurious, as it comes with thick boards, premier paper, and high-quality leather bindings. It also featured printing technology’s new ability to print large graphic illustrations on the same pages as the text. This edition was a critical success.

A & C Black authorized printing, binding, and distribution of the Britannica to American firms of Charles Scribner’s Sons from New York; Little, Brown and Company from Boston; and Samuel L. Hall from New York. But despite this, several hundred thousands of cheaply-produced, bootlegged countries were also sold in the US, which at the time did not have copyright laws protecting foreign publications. They sold Britannica at a very low price, making the originals unappealing to the public. In 1890, leading bootlegger James Clarke published the Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica, Revised and Amended with only ten volumes.

Horace Everett Hooper, an American businessman and a close associate of James Clarke, recognized the potential profit in 1896. Hooper learned that Britannica and The Times of London were in financial difficulties. Hooper partnered with Clarke, Clarke’s brother George, and Walter Montgomery Jackson to sell the Britannica under the sponsorship of The Times. The exceptional profits delighted the manager of The Times, and the partnership sold over 20,000 copies of Britannica in the United States. This caused A & C Black to move to London in 1895, and in 1901, all the rights to Britannica were sold to Hooper and Jackson. The sale of Encyclopedia Britannica to Americans left a lingering resentment to some British citizens.

American Editions – 10th to 14th (1901 to 1973)

At the turn of the 20th century, Britannica is owned and managed by American businessmen who pioneered direct marketing and door-to-door sales. The new owners also simplified the articles, making them less scholarly but easily understood by the masses. The 10th edition was more of a reprint of the 9th, with an 11-volume supplement numbered as volumes 25 to 35.

The renowned 11th edition, which was published from 1910 to 1911 in 28 volumes, was a completely new work. This edition is still a highly regarded scholarly work for its lucid explanations for scholarly subjects. The 11th retained the high scholarship of the 9th edition but dialed it down to simpler articles. This helped popularize the Britannica to the mass market, while still retaining its quality work. Horace Everett Hooper held its scholarship in high regard and worked hard for the 11th edition to be as excellent as possible.

In 1908, Hooper and Jackson had a heated legal dispute over ownership of the Britannica. In the end, Hooper bought out Jackson, becoming the sole owner of the encyclopedia. The public wrangling caused The Times to cancel its sponsorship contract. Hooper managed to get Cambridge University as a new sponsor, so the 11th edition was published initially by Cambridge University, and scholars from the institution were allowed to review the text and had the right to reject any overly aggressive advertising. Because of this, the Britannica underwent financial difficulties. Hooper licensed the Britannica to Sears Roebuck and Co. of Chicago. The owner of Sears, Julius Rosenwald, single-handedly saved the Britannica from bankruptcy a few times over the next 15 years.

During the years of World War I, Britannica experienced poor sales that brought it to the brink of bankruptcy. Thankfully, Julius Rosenwald was devoted to the mission of Britannica and bought its rights from Hooper in 1920.

In 1922, the 12th edition of Britannica was released with a three-volume supplement to the 11th edition, adding articles about World War I and the political changes brought by the war. Hooper died the same year, just a few weeks after the publication of the 12th edition. The edition was a commercial failure, and it lost Sears around $1.75 million. Because of this, Sears gave back the rights of the company to Hooper’s widow and her brother, William J. Cox. The Cox siblings ran the company from 1923 to 1928.

The 13th edition was released in 1926, and it was created as a supplement to the 12th edition. It featured well-known and respected personalities as contributors, such as Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Harry Houdini, Sigmund Freud, Leon Trotsky, Henry Ford, Gustav Stresemann, and more.

Rosenwald brought back the rights to the Britannica in 1928, leaving Cox as the publisher. Sears Roebuck and Co. invested for the 14th edition of the Britannica, because by then the 11th edition was beginning to show its age, and it’s not good to supplement it anymore. The 14th edition, published in 1929, was very different from the 11th, having simpler articles and fewer volumes. All in all, there were roughly 3,500 named contributors for the Britannica, and roughly half were American. It included many illustrious contributors, including 18 Nobel laureates in science and popular personalities in entertainment.

Sadly, the Great Depression struck a month scarcely after the release of 14th edition, causing sales to plummet. Despite the unfailing support of Sears, Britannica almost went bankrupt again. After Rosenwald died in 1932, General Robert E. Wood took over Sears, and the Secretary-Treasurer of the company, Elkan Harrison Powell became the new president of the Britannica.

Powell identified and fixed the critical problem as to why Britannica experienced fluctuating sales problems, which primarily affects the company’s income. After the release of a new edition, sales are generally strong, but it declines gradually for 10 to 20 years as the edition began to show its age. Then, prices drop off with the announcement that works for the new edition is underway, since a few people would buy an outdated encyclopedia that will soon be updated. These fluctuations in sales led to economic hardships and almost-bankruptcies for Britannica.

To address the problem, Powell suggested the policy of continuous revision in 1933. It was done by maintaining a continuous editorial staff that can constantly revise articles, instead of assembling an editorial staff just at the beginning of a new edition. Instead of releasing supplemental volumes or editions, there were new printings made every year that was only enough to cover the sales for that year.

Under Powell’s leadership, the Britannica’s “Book of the Year” was conceived, featuring the developments of the previous year in the changing fields of science, technology, politics, and culture. Britannica’s “Book of the Year” continued to be published until 2018, commemorating the encyclopedia’s 250th anniversary.

The New Encyclopedia Britannica – 15th edition (1974-2010)

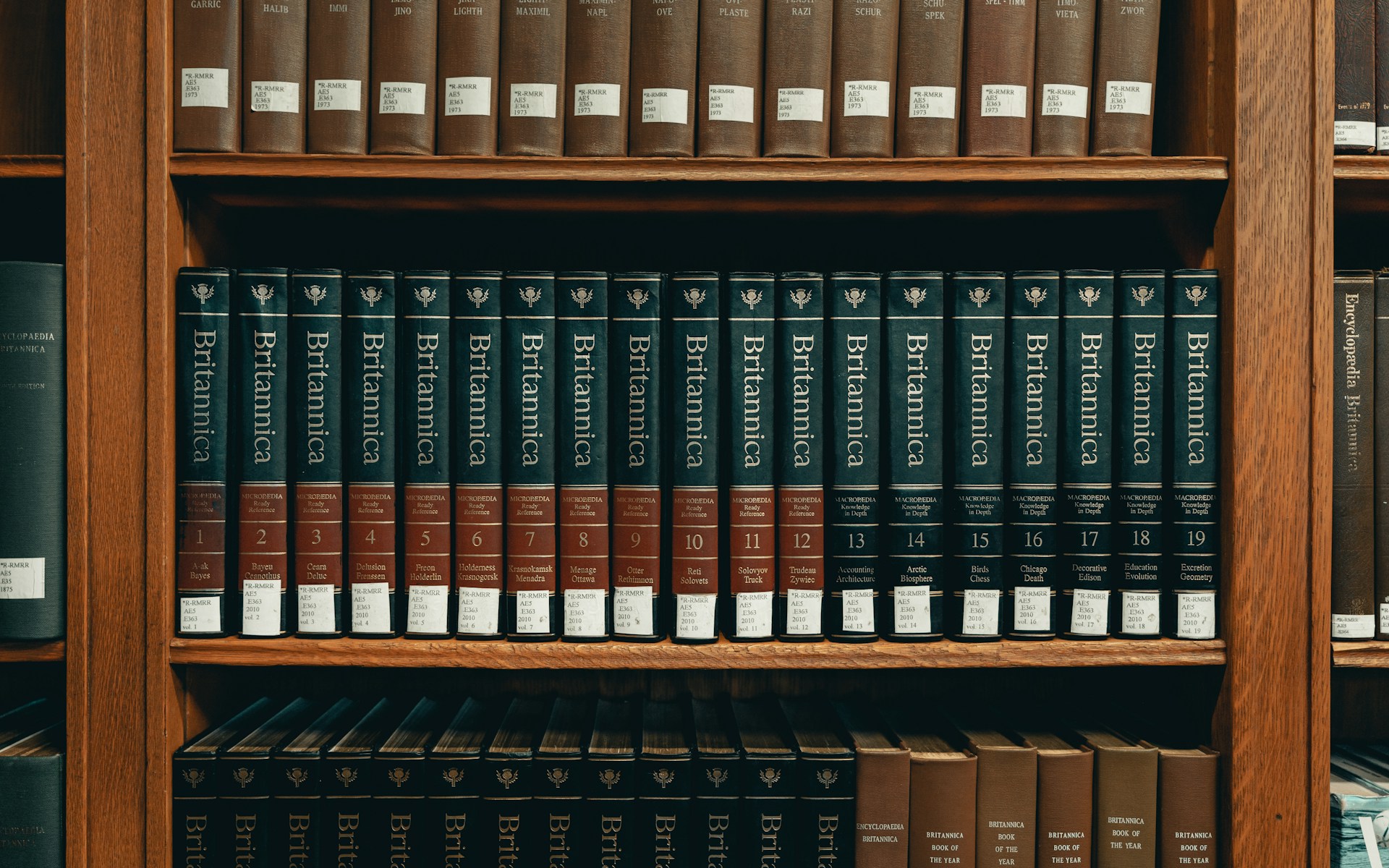

Despite the continuous revision of the Encyclopedia Britannica, the 14th edition gradually became obsolete. The 15th edition was produced over ten years since 1964 and was released in 1974 in 30 volumes. It was called the New Encyclopædia Britannica. This edition was unique because of its new format – it featured a three-part organization to systematize all human knowledge. The 15th edition came with a single Propædia (Primer for Education) volume containing an outline of all knowable information, a 10-volume Micropædia (Small Education) for short articles less than 750 words, and a 19-volume Macropædia (Large Education) for longer, scholarly articles simper to those of the 9th and 11th editions. It also did not have indexes.

However, the absence of an index and the grouping of articles in parallel encyclopedias provoked a lot of criticism for the 15th edition. Most readers cannot predict whether a given subject can be found in the Micropædia or Macropædia, so they have to look it up usually on both. In response, the publishers and editors released a second version of the 15th edition in 1985, reorganized with index restored as a two-volume set. The second version of the 15th edition was released until 2010.

Digital Era (1994-present)

In 1994, an online version of the Britannica was launched. Before this happened, let’s backtrack a little.

In 1980, Microsoft offered Britannica to collaborate on a CD-ROM encyclopedia, but Britannica denied the offer. The senior managers of Britannica were confident in their control of the market, as the product was considered a luxury brand. The management did not believe that a CD-ROM will improve their business. So, Microsoft used content from Funk & Wagnalls Standard Encyclopedia instead and created Encarta, which was released in 1993.

Britannica enjoyed an all-time high of $650 million in sales in 1990. However, during the mid-1990s, Encarta soon became a software staple with every computer purchase. This caused the sales of Britannica to plummet.

The company countered by offering a CD-ROM version of the Britannica, but it cannot generate the sales commissions from print versions. In 1994, they launched an online version of their encyclopedia for sale at $2,000. By 1996, this price was dropped to $200, and sales plummeted to $325 million. As the company faced financial losses, Swiss financier Jacob Safra bought the company for $135 million. Sales of the CD-ROM continued to fall. The online version of Britannica was even offered free of charge on the Internet for around 18 months (from 1999 to 2001) to compete with Encarta.

In 2012, Britannica announced that they would not be printing any more sets of its print version. The last printed versions were published in 2010 and only accounted for 1% of the company’s revenue. Since then, Britannica transitioned to an online or CD version. CD sales ended with the 2012 “Ultimate Edition.”