Japanese internment camps were constructed in the United States under the orders of the government, who wanted to prevent espionage by Japan during World War II. While the intent for creating the camps was for the good of the country, many reports stated that the law allowing the construction of the camps was one of the worst violations of American civil rights in history, as it is inside the camps that American-born Japanese people were poorly mistreated. To know more about the living conditions of these camps, let us take a brief look at the life for people in Japanese internment camps.

The Creation of the Internment Camps

Two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, specifically in February 1941, then-US president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which allows the creation of internment camps along military zones in Washington, Oregon, and California. These internment camps would be utilized to relocated Americans of Japanese ancestry to a controlled camp wherein they will be monitored for possible espionage in the United States from the Japanese government.

Executive Order 9066 was supposed to incarcerate not only Japanese Americans but also Italian Americans and German Americans, but because it was difficult to distinguish people with Italian or German ancestry, the officials in charge of putting people in the camps only focused on Japanese Americans.

Incarceration of Japanese Americans

In March 1942, the War Relocation Authority was established to have a proper system for incarcerating Japanese Americans in the United States, as it was known during the latter days of February that about 15,000 Japanese Americans were fleeing restricted areas in order to not be sent in the internment camps. By March 24, the War Relocation Authority sent a six-day notice to the Japanese Americans to bring what they could carry in the camps and dispose of items that they could not. The Japanese Americans would then need to stay at assembly centers, which are set up near their homes. After a few days, they would be transferred to a relocation center that serves as the internment camp.

The living conditions for all of those places, including the assembly centers and the relocation centers, were not great, as they are constructed in locations that are unsuitable for human living, such as cowsheds, horse stalls, and barns. One of the assembly centers built during that time was at the Pacific International Livestock Exposition Center (known today as the Portland Expo Center), wherein about 3,000 stayed there before being transferred to an internment camp. In addition, one of the biggest assembly centers in the United States was the Santa Anita Assembly Center in Los Angeles, where it was reported that 18,000 Japanese Americans were brought there, and that about 8,000 people lived in dirty stables. Because of the staggering number of people living in the said assembly center, the place was suffering from poor sanitation and food shortages.

Working at Assembly and Relocation Centers

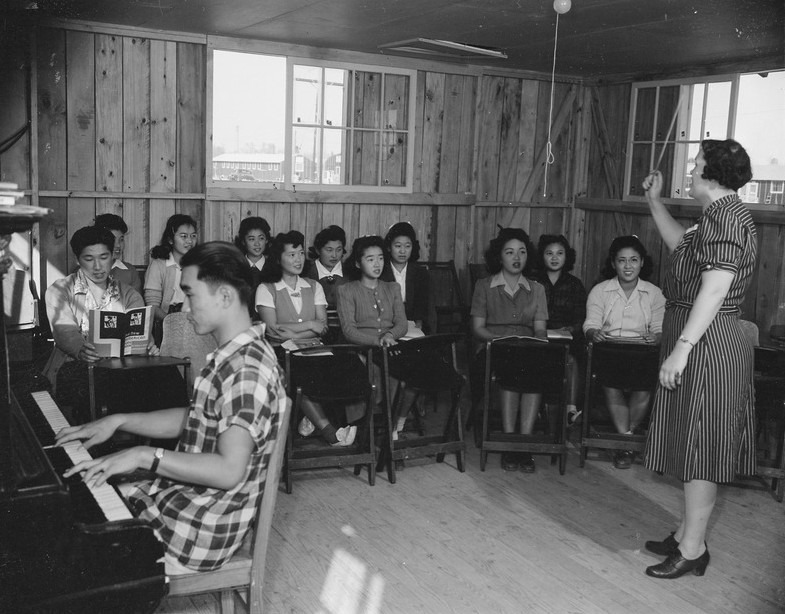

Officials in charge of facilitating assembly centers offered the Japanese Americans jobs, although the salary that they get for labor was less than what an Army private gets. By offering the incarcerated people jobs, they will be able to minimize labor costs in the assembly centers while offering a sense of “normality” for the Japanese Americans. There were different jobs that the Japanese Americans took while inside the assembly centers, and those jobs include being a mechanic, a doctor, and even a teacher for children inside the centers.

As the country was experiencing labor shortage due to the number of men sent to war, specifically in farms, the government set up assembly and relocation centers in farm-focused states in the US so that the Japanese Americans will be tasked to do farm duties. It is believed that over 1,000 internees were sent to farms to harvest crops and perform other farm-related work.

Living Conditions in Relocation Centers

In the United States, there were about ten relocation centers that were constructed in several states around the country. Some of the relocation centers were built like barracks, where families will have their own space to live in. But the relocation centers would have communal eating areas so that they will be better monitored and their food will be regulated.

Besides the barracks, the relocation centers also have post offices, factories, and even schools where children can continue their education. To have a better supply of food, the center would usually have farmlands where the Japanese Americans can work as farmers to harvest crops and keep livestock.

Although these internment camps look like they have good living conditions, the violence and racism that happens within the camps were notoriously rampant. There were some Japanese Americans that tried to flee the camps from 1942 to 1943, and some of those escapes resulted in their death at the hands of the military police monitoring and guarding the camps.

End of the Internment Camps

The internment camps were abolished in 1945 after a Supreme Court decision on the “Endo v. the United States” case, which was filed by a Japanese American named Mitsuye Endo. Before the decision, the Supreme Court has already ordered President Roosevelt to close and demolish the camps so that he can announce the camps’ closure before the Supreme Court announces their decision.

Despite putting an end to the camps, the Executive Order 9066 remained active until 1976, when President Gerald Ford repealed it. As an act of formal apology, the US Congress gave more than 80,000 Japanese Americans that were incarcerated in the camp $20,000 each, which was made possible through the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.